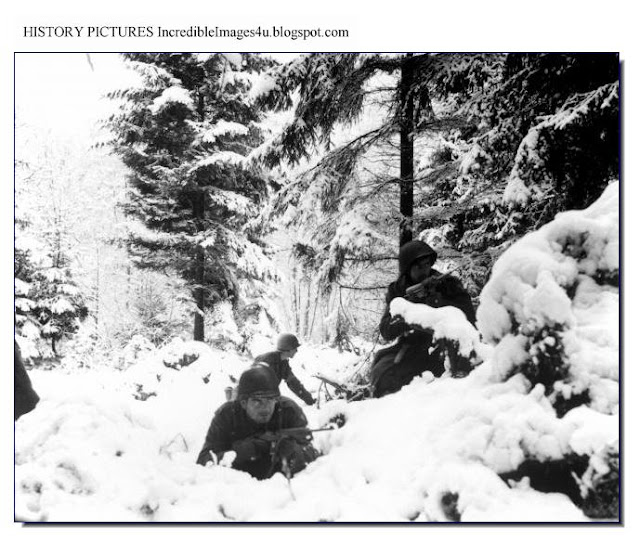

The German troops on the move during the Ardennes Offensive

WHAT WAS THE ARDENNES OFFENSIVE?

Battle of the Bulge, popular name in World War II for the German counterattack in the Ardennes, Dec., 1944–Jan., 1945. It is also known as the Battle of the Ardennes. On Dec. 16, 1944, a strong German force, commanded by Marshal von Rundstedt, broke the thinly held American front in the Belgian Ardennes sector. Taking advantage of the foggy weather and of the total surprise of the Allies, the Germans penetrated deep into Belgium, creating a dent, or "bulge," in the Allied lines and threatening to break through to the N Belgian plain and seize Antwerp. An American force held out at Bastogne, even though surrounded and outnumbered. The U.S. 1st and 9th armies, temporarily under Field Marshal Montgomery, attacked the German salient from the north, while the U.S. 3d Army attacked it from the south. Improved flying weather (after Dec. 24) facilitated Allied counterattacks. By Jan. 16, 1945, the German forces were destroyed or routed, but not without some 77,000 Allied casualties.

THE STATE OF THE WAR THEN (From Worldwar2database)

By the end of 1944 Germany was losing on all fronts. Her generals, faced with ever increasing armies armed with superior technology, fell back under the combined assaults in Italy, the Eastern Front, and France.

The famous picture of the German soldier in Ardennes. The desperation shows on the face

WHAT WAS THE PLAN?

Optimism was absent from the German command. In September 1944, as the Russians halted their advance on Warsaw and the Allies stalled in Holland in Operation Market-Garden, Hitler stunned his generals with a bold plan reminiscent of the 1940 campaign. Panzer divisions backed by Volksturm units would smash through the weakly defended Ardennes and head for Antwerp, cutting off the Allied supply lines. Special English-speaking units in modified German armor and captured American equipment would range out ahead of the Panzers, causing confusion and creating fear among the ranks.The bold plan included a large, desperate attack by the remaining Luftwaffe units on the Allied airfields.

An American soldier peers out of the window. Below lies a dead German soldier

His generals demurred, arguing the attack would never succeed. Hitler overruled them. A buildup in Germany’s Eiffel region began, draining tanks and men from other fronts. Most of these soldiers were fifteen and sixteen years old.

A German APC vehicle moves. In the background is the ruin of a M 10 American tank.

HOW IT WENT

The Americans had only a few divisions, including the 106th division, in the Ardennes guarding a fifty-mile front. The area was used to rest and refit divisions coming off the line, or to organize new units. The Germans poured fourteen infantry divisions and five Panzer divisions into this front, smashing the new 106th division out of existence. 7,500 men surrendered in the largest American mass surrender in the European Theatre of Operations.

American soldiers move. America lost many soldiers in the Ardennes Offensive

BASTOGNE

They were to hold the town with little supplies and few tanks or vehicles. A store of flour in a Belgian warehouse fed the 101st with flapjack pancakes. American GIs retreating from the German advance stopped and joined in the defense. Artillery was set up in the center of town to give the defenders support anywhere along the lines, and from their arrival on December 18th until the day after Christmas, the 101st beat back German attacks. During the battle, the German commander charged with taking the vital crossroads sent a long letter to General Anthony C. McAuliffe, calling for his surrender. McAuliffe’s one-word reply, “NUTS!” indicated the determination of the 101st to hang on.

The caterpillar tracks of the American tank have come out

Montgomery took full credit for saving the American armies during the battle, and insinuated that he had “handled” the battle. He also managed to knock American leadership. Bradley, Eisenhower, and Patton were furious. Churchill had to make a public statement to the House of Commons to calm things down praising the Americans for the their conduct in the battle.

It was an American battle. The largest battle in the West during the war, some 600,000 Americans fought it, and 80,000 were killed, captured, or wounded. The Germans lost 30,000 dead, 40,000 wounded, and 30,000 were POWs.

Hitler lost some of his personal prestige, as it was his plan. The failure of the Ardennes meant that those tanks and soldiers would not be available for the defense of Germany herself. Hitler’s gamble shortened the war by months.

Albert Speer, Reichminister for Armaments and War Production, wrote, “The failure of the Ardennes Offensive meant that the war was over.”

American soldiers in winter camouflage clothing. The 101st Division of the American Army was encircled by German troops in Bastogne but they managed to hold it

These Germans have surrendered

American troops get dry rations

Montgomery had tried to get all the credit for halting the Ardennes Offensive. The American generals were livid.

The Malmedy Massacre.

WHAT WAS THE MALMEDY MASSACRE?

The Malmédy Massacre occurred on December 17th 1944. The Malmédy Massacre took place during the Battle of the Bulge and was one of the worst atrocities committed against prisoners of war in the West European sector during World War Two.

About half-a-mile from the 'Baugnez Crossroads', the first vehicles in the convoy were fired on by two tanks from the 1st SS Panzer Division led by Joachim Peiper. This unit was one of just two units in the whole Nazi military allowed to use Hitler's name in its title - the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler. This unit had a fearsome reputation and Peiper was known as a man who would let nothing stand in his way of success - including the taking of prisoners. In the Russian campaign, Peiper's unit was known as the 'Blowtorch Brigade' for its violence towards civilians.

On this day in particular, it is said that Peiper was in a particularly foul mood as his advance had not been as successful or as swift as he had hoped. Though the 1st SS Division had suffered few casualties in terms of manpower, it had lost tanks and half-tracks in its advance as the US 99th Infantry Division had put up a far stronger resistance than Peiper had bargained for. The two tanks that fired on B Battery were under the command of SS Lieutenant Werner Sternebeck. He had lost five of his seven tanks in the advance. Peiper, it seems, was furious at yet more delays to his advance.

Clearly outgunned by the Germans, the men from B Battery surrendered after Sternebeck's attack. Peiper himself went to the Baugnez Crossroads and brusquely ordered Sternebeck to move on. The 113 American prisoners-of-war who had survived the attack were assembled in a field near the Café Bodarwé at the crossroads - this figure included eight Americans who had already been captured by Peiper. A young Belgium boy witnessed what happened next.

At about 14.15, soldiers from the 1st SS Panzer Division opened fire on the 113 men who were in the field. The firing stopped at about 14.30. Soldiers from Peiper's unit went around the field and shot at close range anyone who seemed to be alive - or clubbed them to death as later autopsies showed. Incredibly, some prisoners did get away after feigning death. It was three of these escapees that came across Pergrin.

THE TWO THEORIES ABOUT THE MASSACRE

The men were deliberately murdered in cold blood. Certainly, the 1st SS Panzer Division had been responsible for atrocities in Russia and they had already shot captured Americans in their advance in the Ardennes Offensive - and more were shot after Malmédy. It is possible that Major Werner Poetschke, who commanded the 1st SS Panzer Battalion, gave the order - but no evidence has proved this, just rumour.

Another theory put forward is that some Americans tried to escape and were fired on by the Germans. Other Germans heard the firing, but were not aware that the targets were three Americans as opposed to all of the group. Either trigger-happy or simply battle-hardened, they opened fire on the group as a whole. In October 1945, an American soldier made a sworn testimony that he had escaped with two other men (who were killed) but he had survived and made it back to US lines. The law as it stood then would have allowed the Germans to shoot at escaping prisoners - but not at the whole group. It is possible that their escape precipitated the shooting of the other men.

On this day in particular, it is said that Peiper was in a particularly foul mood as his advance had not been as successful or as swift as he had hoped. Though the 1st SS Division had suffered few casualties in terms of manpower, it had lost tanks and half-tracks in its advance as the US 99th Infantry Division had put up a far stronger resistance than Peiper had bargained for. The two tanks that fired on B Battery were under the command of SS Lieutenant Werner Sternebeck. He had lost five of his seven tanks in the advance. Peiper, it seems, was furious at yet more delays to his advance.

Clearly outgunned by the Germans, the men from B Battery surrendered after Sternebeck's attack. Peiper himself went to the Baugnez Crossroads and brusquely ordered Sternebeck to move on. The 113 American prisoners-of-war who had survived the attack were assembled in a field near the Café Bodarwé at the crossroads - this figure included eight Americans who had already been captured by Peiper. A young Belgium boy witnessed what happened next.

At about 14.15, soldiers from the 1st SS Panzer Division opened fire on the 113 men who were in the field. The firing stopped at about 14.30. Soldiers from Peiper's unit went around the field and shot at close range anyone who seemed to be alive - or clubbed them to death as later autopsies showed. Incredibly, some prisoners did get away after feigning death. It was three of these escapees that came across Pergrin.

THE TWO THEORIES ABOUT THE MASSACRE

The men were deliberately murdered in cold blood. Certainly, the 1st SS Panzer Division had been responsible for atrocities in Russia and they had already shot captured Americans in their advance in the Ardennes Offensive - and more were shot after Malmédy. It is possible that Major Werner Poetschke, who commanded the 1st SS Panzer Battalion, gave the order - but no evidence has proved this, just rumour.

Another theory put forward is that some Americans tried to escape and were fired on by the Germans. Other Germans heard the firing, but were not aware that the targets were three Americans as opposed to all of the group. Either trigger-happy or simply battle-hardened, they opened fire on the group as a whole. In October 1945, an American soldier made a sworn testimony that he had escaped with two other men (who were killed) but he had survived and made it back to US lines. The law as it stood then would have allowed the Germans to shoot at escaping prisoners - but not at the whole group. It is possible that their escape precipitated the shooting of the other men.

In January 1945 after it was all over; German POWS carry the body of an American soldiers

GERMAN NEWSREEL ON ARDENNES OFFENSIVE: PART 1

PART 2

No comments:

Post a Comment